Finally, why do roads jog at some intersections?

Posted on February 17, 2021

Part 3 of 3

In the first two articles of this series of three, we have established that there would be error in the surveys. Regardless of the skill and care of the surveyor, error would accrue from the following sources:

- Environmental conditions.

- Instrument limitations.

- Creating square townships on a spherical surface.

It was understood that avoiding error, or correcting all error, would be impractical, if not impossible.

Surveying is more than measuring. We are all taught at a very young age how to measure with a ruler. The skill of surveying, almost an art, is understanding the nature of errors in measurement, understanding the tolerance for error on a project, and designing a surveying solution that minimizes the error and satisfies the client’s objective. It would be nice if every survey was without error. But the effort and cost to remove all error would drive up the cost of the project and extend the completion time. A good surveyor provides the client with a survey that is accurate for the intended purpose.

Edward Tiffin was the Surveyor General in 1815 when the original surveys began in Michigan. He understood that the surveys needed to be completed in a timely manner. The expansion of civilization into the western lands was dependent on the completion of the surveys. Instead of removing as much error as physically possible, Tiffin issued a set of instructions in 1815 to all surveyors, detailing the procedure for the surveys of government lands, and specifically cited how to constrain error. The objective was not to remove the error, but to constrain the error.

Error caused primarily by environmental conditions and instrument limitations would be confined to the limits of the six-mile “square” township. The perimeter of the township would be created first, setting wooden posts every half mile. Then the surveyors were instructed to start on the south line of the township at a specified section corner (wooden post) and then survey north to the corresponding section corner on the north line of the township, six miles away, through whatever terrain awaited them. The surveyors were also instructed to mark the line surveyed by making cuts, or “blazes”, on trees, setting wooden posts every half mile and noting all significant features such as rivers, cliffs and “Indian trails”. By the time the surveyors reached the north line, it was unlikely that they would arrive exactly at the correct location.

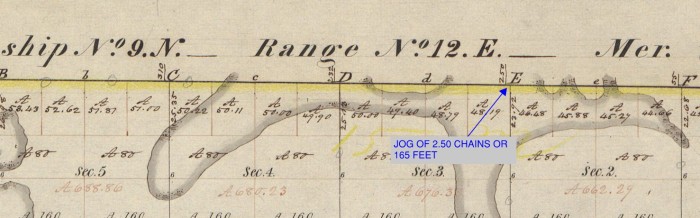

Tiffin decided to allow the error to remain, as long as it was not deemed to have been the result of a significant mistake or a “blunder”. However, when proceeding to the next township to the north, the correct corner would be used so that all of the error accrued in the township to the south would stay in the township to the south. The effort to go back and make all of the corrections to try and reduce the error, would greatly increase the time needed to complete the surveys. So, along the perimeter of every township surveyed under Tiffin’s 1815 instructions, there is likely to be error. It may be only a few feet, or it could be a hundred feet. But that error or more accurately, “adjustment” still exists today.

The surveyors were instructed to run their lines along a due north line. This intentionally causes the surveys to run along lines that were not parallel, but were heading towards the same point, the North Pole. If the surveyors were able to survey with out any error cause by instrument limitations or environmental conditions, all lines would converge as they progressed further north. This is called “Convergence of the Meridians”. From the south line of a township to the north line of a township six miles away, the 1-mile width of a section would be reduced by about 43 feet, in southern Michigan (it would be greater further north). To adjust for Convergence of the Meridians, Tiffin decided to correct all township to a full 6-mile width at lines call “Correction Lines” or “Standard Parallels”. These east/west correction lines would occur after every 10 townships as the surveyors proceeded north, or every 60 miles. The Convergence of Meridians over these 60 miles would cause a section that is exactly 1-mile wide at the baseline to be 445’ shorter at the first correction line, 600’ to the north.

Based on these errors, and how the 1815 Instructions required the surveyors to control these errors, section lines are expected to jog at township lines and at correction lines. Over the years, these section lines became roads, creating the 1-mile square road pattern that is familiar to many of us in southeast Michigan. Since the roads follow the section lines, and the section lines jog due to the error control measures employed by the original surveys of Michigan, then the roads also jog. It is common for municipalities to reduce the effects of this jog by making the road curve, or adding a roundabout. Regardless of the method used to build a road through these jogs, the jogs are intentionally there due to the vision and effort of the General Land Office in the performance of the original surveys of the Public Land Survey System in Michigan.

My official signature block says, “Craig P. Amey, PS, Senior Project Surveyor”. I looked up “Senior” in my Encyclopedia Britannica and the definition included words like “elderly”, “older” or the ever-comforting phrase, “in their final years”. Normally, this wouldn’t bother me much, but with the renovations of our office, they replaced my chair with an easy-up recliner, my desk with a TV tray, and my computer with a Sudoku book. Now they’ve asked me to contribute to something called a blog. I am supposed to write about our surveying department and put it on that internet thing. I guess I can write a thing or two, because as the insurance company says, “I’ve seen a thing or two”. I guess I better get writing, right after my nap.