Why do Roads Jog? Part 1 of 3

Posted on October 12, 2020

You have the wife and kids packed into the station wagon. It’s a nice fall day, and you are out for a drive. The wife is reminding you that when you get home, the trash needs taking out, the lawn needs mowing, the windows need cleaning, and on and on. In the back seat, the children are having a screaming match over backseat turf boundaries. Through the mirror, you can see the family dog in “the way back” with a sandwich from the picnic basket. Nearly at your wits end, you come to an intersection in the road. You want to go straight through, but you can’t. The AAA Trip Ticket says that the road goes straight through, but ahead you can only see corn. Then you see that the continuation of the road that you are on, the road that should be straight according to AAA, jogs about 100 feet to the east. “Why?” you scream at the road. Your wife falls silent, the kids stop screaming, and the dog, well the dog just keeps eating the sandwich. This is a scenario that has played out for a couple hundred years, and this is why.

The year is 1815. Our foundling nation is only a few decades old. Much of that time was spent engaged in conflict with England, France, and Native Americans. As a result, our young nation owed a great debt to its soldiers. It was a debt that could not be paid in cash. The new US treasury was not rich in currency. But it was rich in other ways. Most importantly, it was rich in land. The US could give land in lieu of cash to soldiers. On May 6, 1812, Congress passed two Acts setting aside lands in Michigan and other states to be used as payment to soldiers for their service to the United States during the War of 1812. In these Acts it was clear about how much land was to be given to each commissioned, non-commissioned, private, or musician (up to 160 acres). However, it was not defined how that land was to be divided or designated.

Thomas Jefferson, a Founding Father of our nation, the third President of the United States, and even better, a surveyor, had an idea. The whole concept of weights and measures had long intrigued Jefferson. This is evidenced by his submittal of the “Plan for Establishing Uniformity in the Coinage, Weights and Measures of the United States” in 1790. Jefferson had one goal in mind with measuring the lands of the United States: it had to be simple for the common man to reproduce. What could be simpler to measure than squares and rectangles?

In 1784, a Continental Congress committee, chaired by Thomas Jefferson, submitted a report that outlined the system for surveying the “Western Territory”. Although Jefferson, a strong advocate of the metric system, originally wanted a system that included 10-mile square townships, the final report included townships that were 6 miles square and subdivided into thirty-six 1-mile squares called “Sections.” Jefferson also called for the banning of slavery in all new states, but the Continental Congress rejected this proposal.1

The report, as approved by the Continental Congress, would direct the survey of the lands owned by the United States as a result of their Revolutionary War victory and their independence. The lands in the original thirteen colonies had already been surveyed and transferred into private ownership, along with lands located along water routes, called “Private Claims”, in the western lands. The lands already owned would not be included in the survey of US lands, known as the Public Land Survey System (PLSS).

The man in charge of implementing the PLSS was the US Geographer Thomas Hutchins. On September 30, 1785, Hutchins was joined on the north bank of the Ohio River on the western boundary of the State of Pennsylvania by surveyors from the colonial states. They began the survey of an east-west line, now known as the “Geographers Line”, into an area that would become Ohio. This survey was the beginning of the PLSS.2 (Incidentally, the survey of the US public lands continues today in remote areas of Alaska, which must make the PLSS the longest continuous public works program in US history.)

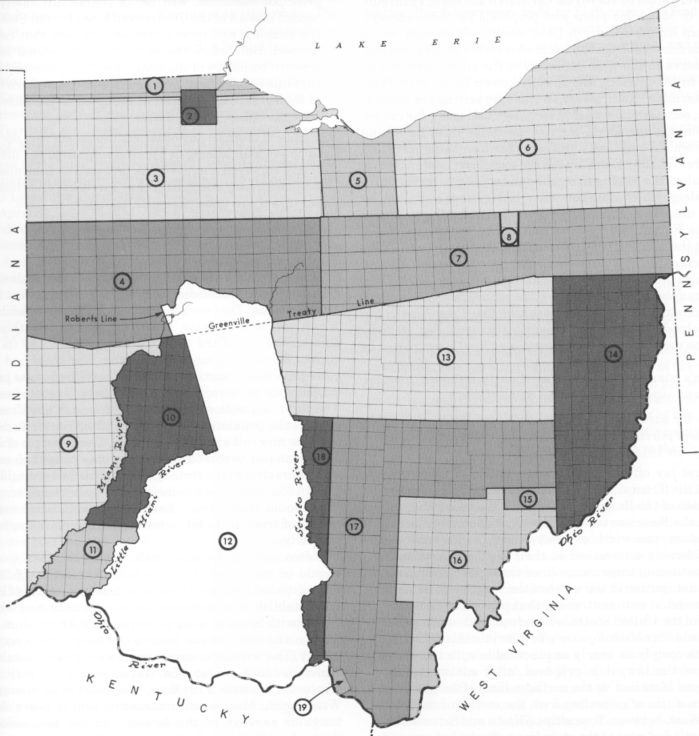

The Geographers Line was the beginning of the PLSS, but questions still remained about the exact method of dividing the land into rectangles. Ohio was the test area for land division methods. There are 19 different methods of land divisions in the State of Ohio2.

By the time the surveys in Ohio were complete, a method had been determined that would be used for the remaining lands. It was not a perfected system, and it would require a number of changes, but the basic concept had been decided. On April 18 and 28, 1815, the Surveyor General (formerly US Geographer), Edward Tiffin contracted with Alexander Holmes and Benjamin Hough to begin the surveys of the first area to be completely surveyed under this refined system. This area would eventually become the State of Michigan.

In Part 2 of 3 of “Why Do Roads Jog”, the surveying of Michigan, and its abrupt end just as it started, will be presented in future posts.

References:

1. Library of Congress, “Incorporating The Western Territories”, https://rb.gy/nr4fyi, Acquired September 2, 2020.

2. United State Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management, “A History of the Rectangular Survey System”, https://www.blm.gov/sites/blm.gov/files/histrect.pdf, Acquired September 2, 2020.

My official signature block says, “Craig P. Amey, PS, Senior Project Surveyor”. I looked up “Senior” in my Encyclopedia Britannica and the definition included words like “elderly”, “older” or the ever-comforting phrase, “in their final years”. Normally, this wouldn’t bother me much, but with the renovations of our office, they replaced my chair with an easy-up recliner, my desk with a TV tray, and my computer with a Sudoku book. Now they’ve asked me to contribute to something called a blog. I am supposed to write about our surveying department and put it on that internet thing. I guess I can write a thing or two, because as the insurance company says, “I’ve seen a thing or two”. I guess I better get writing, right after my nap.